Written by our Guest Facilitators, Dr Olga Kozar and Geraldine Timmins from Macquarie University

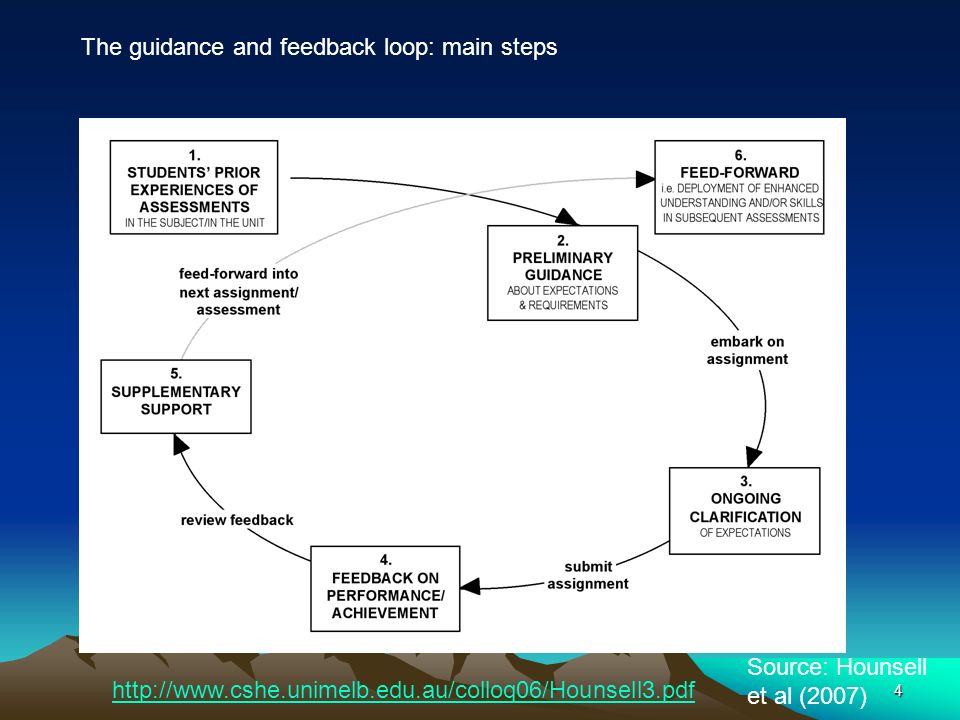

As discussed on Day 1, a crucial element of effective feedback is whether students can use it in their current work. Anything students can employ immediately tends to have a much stronger impact than ‘general’ tips for the future.

Reflection Question

Reflection Question

Have you noticed any difference in how your students use your feedback based on when in the semester you’ve provided it?

Share your thoughts in the comments!

Tip 1: Early feedback gets the… results!

Staging (= breaking down) assessments and giving students opportunities to regularly present their work-in-progress to peers and educators for feedback is good teaching practice. Not only will it help students manage their assignments (and time!) better, it’ll also work towards reducing ‘contract cheating’, and other forms of academic dishonesty.

For example, one approach is to break down a major assignment into several sub-tasks and specify a given task each week.

E.g.“This is a good week to do the literature review on your topic, and identify a gap that you’d like to explore in your assignment. Please prepare a one-paragraph summary of your literature review and be ready to share it in our next tutorial”.

The following week, students can prepare bullet points of the key arguments they’ll present in their assignments followed by a group discussion about those points, etc.

Research also suggests that when students are ‘novices’ in a discipline, they need extensive feedback on strategies and effort to ‘keep them going’ (Shrunk & Rice, 1991). As students become more experienced and confident, they often do not need as much ‘cheer-leading’ to complete a task, so the feedback on ‘effort’ can be reduced.

Time-saving Hack

Shift the bulk of feedback from the ‘end of semester’ assignments to an earlier time, and make feedback ongoing.

Tip 2: Have a ‘soft submission’ deadline

Another way to provide ‘feed-forward’ is having a soft deadline for an assessment submission. For example, students could bring a full draft of their work to the tutorial a week before an assignment is due and discuss it in class.

The educator could lead the discussion by asking targeted questions and using the criteria from the rubrics.

The educator could lead the discussion by asking targeted questions and using the criteria from the rubrics.

Asking questions such as “On this scale [from the rubric], how clear is the main argument of this work? How well are different perspectives integrated?” will not only maximise opportunities for self-assessment and reflection (which can be even more impactful than external feedback – see Boud & Falchikov, 2007; Li, Liu, & Steckelberg, 2010), but it will remind students about the specific criteria used to grade their work.

Educators could also provide anonymised samples of similar assignments and use these to ‘model’ peer review, or to present common mistakes made on past assignments. The key is to get students thinking as reviewers and assessors and is a chance to provide some individualised early feedback prior to assessments.

Tip 3: Get students to self-assess before they receive their marks

Ask students to assess their final submission using the rubric and reflect on their assignment before they submit or receive their marks.

As we saw in Day 2, self-assessment is an effective strategy to ensure students engage and understand your feedback (Boud & Molloy, 2013).

Asking students to use the marking criteria and write their own general feedback or reflection can significantly improve how much they engage with feedback. It will also give educators a useful starting point for feedback, as you can identify the key issues and misconceptions and address them in your own comments to students.

Similarly, several studies (e.g Gruhn and Cheng, 2014; Montepare, 2005) report that giving students an opportunity to analyse their mistakes and reward them with additional marks is another way to improve learning. In their study, they allowed students to submit their exam answer sheet, take a copy of the exam paper home and prepare another version of their answers. Both ‘in-class’ and ‘at-home’ exams were scored, and a cumulative mark awarded.

Similarly, several studies (e.g Gruhn and Cheng, 2014; Montepare, 2005) report that giving students an opportunity to analyse their mistakes and reward them with additional marks is another way to improve learning. In their study, they allowed students to submit their exam answer sheet, take a copy of the exam paper home and prepare another version of their answers. Both ‘in-class’ and ‘at-home’ exams were scored, and a cumulative mark awarded.

Given the time investment required for double-scoring, we’d like to suggest a modified version of this approach: why not get students to identify 2-3 key potential mistakes that they may have made, write up in their own words why this happened, and what they could have done differently. This reflective piece could be submitted via Turnitin, and be awarded additional marks.

Tip 4: Have an exam or final assignment debriefing

Exams and final assignments can be a valuable learning opportunity, but, more often than not, students hand in the papers, get a grade… and that’s it.

If your students go on to do similar assessments in the future (chances are they will), this provides a valuable opportunity to provide feedback they could benefit from in a different subject, course or context.

Examples: If your students have an exam, you could arrange a 15-30 minute Q&A session with the whole cohort or class, straight after the exam (e.g. 10 minutes after the papers are handed in) ideally to foster peer-to-peer discussion.

Alternatively, you could have a ‘debrief’ (face-to-face or webinar) very soon after the papers have been marked and before grades are released.

As we touched in Day 1, not receiving feedback, or not receiving it in time enough to bring a student back on track, can have hugely detrimental effects.

A personal story:

When I (Geraldine) was doing my first degree (a highly competitive performance-based degree), I received a great mark on my first assignment so thought I was on track. But in the next part of the unit I was having difficulty with a main skill we needed to develop. I’m sure my educators could see I was having difficulty with the work, but they didn’t say anything. I ended up failing the unit (and I couldn’t proceed to 2nd year; the assessments were unusually weighted in this course) and I was utterly shocked and devastated.

Being 19 at the time, I wasn’t self-aware enough to know how to seek help or ask how to improve. My educators could have invited me to reflect on why I was experiencing difficulty or given me pointers on how to move through it. Other students got warnings but I got nothing. I felt like my educators failed in their duty of care to provide key feedback when they could have. The incident has marked me ever since and made me a real advocate for the importance of providing high quality feedback to students with time enough for them to benefit from it.

Discussion Questions:

Discussion Questions:

- Which of the above-mentioned strategies might work in your teaching?

- What are some possible issues you might encounter from using these techniques? How might you address them?

- Are there any other ‘timing-related’ tips that you could share with our community?

Join us for a hands-on workshop with our facilitators!

Tuesday 28 August 1.30-3.00pm

This interactive workshop on “effective feedback”, will guide participants through scenarios of verbal and written feedback, invite the group to collaborate on ‘sustainable’ and good practice examples, and create individual action plans.

Afternoon tea will be provided. Space is limited, registrations are essential for booking and catering purposes.

Go here for more info or to register.

References:

Gruhn, D. and Cheng, Y., (2014). A self-correcting approach to multiple-choice exams improves students’ learning. Teaching of Psychology, 41 (4), 335-339.

Montepare, J. M., (2005). A self-correcting approach to multiple-choice tests. APS Observer, 18 (10), 35-36.

Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2007). Rethinking assessment in higher education: Learning for the longer term: Routledge.

Li, L., Liu, X., & Steckelberg, A. L. (2010). Assessor or assessee: How student learning improves by giving and receiving peer feedback. British journal of educational technology, 41(3), 525-536.

Mahoney, P., Macfarlane, S., & Ajjawi, R. (2018). A qualitative synthesis of video feedback in higher education. Teaching in higher education, 1-23. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1471457

15 thoughts on “Day 3: Feedback timing”

I have used the early feedback approach, by having students answer weekly questions on their assignment topic. Other students are then required to comment and I then provide a sentence or two. To make students actually do this there is 1 mark per week. Next time I am proposing to increase this to 2 marks per week (total of 20% of the final grade).

I found a ‘soft submission’ deadline did not work. The struggling students who would would benefit from feedback on a draft never presented one. So I made it a hard deadline with 10% for the draft, then 30% for the completed assignment. That was a bit much, so I plan to reduce it to 5% for the draft next time. The self-assessment might form a useful part of this process.

I provide the class with general comments on the final assignment, as well as the individual ones to each student. But I doubt these are of much value, as students quite rationally consider the course over. As a student myself I paid little attention to the final assessment feedback, unless I considered my grade inadequate. Even then I would just take my frustration out with a low rating on the course and instructor survey, I would never appeal the mark.

Thank you, Tom! I find your experience with ‘soft submission’ particularly valuable. It may indeed be worthwhile to allocate marks for it to get ALL students take it seriously.

I have used the early feedback approach too. Instead of mid-semester exam, I offered three optional and redeemable quizzes in tutorial from week 4 to week 6. Students have the chance to understand what key concepts they are expected to grasp. I also make the final assignment into two components. In week 7 students submit one key component (may be in a not so refined condition). I will provide feedback in the following 1 -2 weeks. They have enough time to incorporate these feedback into the final submission which weighs much higher than the first assignment. This approach provides students valuable learning opportunities and timing wise, it helps them to prepare for the final exam too.

Thank you, Hua Deng! Could you tell us a bit more about the ‘redeemable’ quizzes? Any thoughts/insights on them?

I definitely will try the self-assessment in the next assignment. It brings the attention to what’s important, rather than a grade.

I do find with the early feedback strategies, especially with the assignment, may put a lot of pressure on lecturer. Students would be eager to find out how they have performed and the lecturer has to finish marking of lots of assignments over a short time. I found my experience quite intense to take care of both timing and quality of feedback.

Last year we (I co-convene a course) tried having a mid-semester exam to both provide early feedback (for us and the students) and break up the course content to reduce the breadth of topics the students needed to study for the final exam. However it backfired. They found the questions difficult and it seemed to fuel general panic in many students relating the expected level of knowledge required for the course. Even though we held an exam debriefing session it turned into a very heated discussion with a vocal minority of students complaining the assessment was unfair. Unfortunately this then set a very negative tone for the remainder of the course, despite out best efforts to provide extra support prior to the final exam.

Having learned from this experience, this year we have removed the mid-semester exam and moved to having revision tutorials where the students work through mock exam questions. We start these in the first few weeks, so they have time to get up to speed before the final exam. This also helps to identify students that might be struggling.

I like the idea of asking students to assess a peer’s work, which they could then get either marks or bonus marks for. I am currently thinking how we might be able to incorporate this into our revision tutorials for next year.

Hi Julia,

Thank you for sharing your experience with the ‘mid-semester’ exam. I was wondering to what extent the negative reaction was due to the assessment type (exam), which tends to be pretty final. In an exam situation, you get assessed and you get a mark. The idea of an ‘early’ feedback is, in fact, a bit different. It’s giving students feedback BEFORE they submit so that they get a chance to identify where they are not doing so well and could improve on those areas. So , instead of an exam, I would consider other types of activities to provide early feedback.

I have used some of these strategies in my teaching. I find that breaking up the assessment and requiring students to submit an essay plan, literature review, annotated bibliography and similar during the course often works well. These earlier assessments count towards the final result, so the students take them seriously, and it allows me to give them comments that they can incorporate in the same course. However, one problem with this approach is that students may be confused whether or not they are allowed to ‘self-plagiarise’ themselves from one submission to the next. For these types of assessments to make sense students must be allowed to build on the text from one submission to the next, but this goes against the general university policy which is (rightly) very strict that they are not allowed to reuse material from one essay to the next.

I like the idea of ‘soft deadlines’ and use this for a series of workshops for master thesis students, but I don’t think the same approach would work in larger groups of students because of limited class-time. In bigger groups I have brought in ‘samples’ of introductions, essay plans etc., and asked the students to evaluate them against a set of criteria. Hopefully that goes some way towards helping them to identify what we are looking for in an essay before they actually have to submit their own.

I think a debriefing might work in my teaching. In one of my tutorial, many students claimed they had learned a certain content in different courses. I then gave them a chance to build the basic model. It turned out most of them gave a wrong answer. So end-of-semester exam does not mean end-of-study. A debriefing might help their future study in this area.

I also find self-assessment attractive. What I am concerned with is that, for our problem-solving subjects, it might be difficult for the students to identify the mistakes. Many colleagues share the idea that ‘the real challenge is not to answer the student’s question, but to identify where the real problem is’. It might be following a wrong logic or misunderstanding an earlier definition. So the instructions of the self-assessment should discourage general mistakes (not working hard, bad time management) and guide the students to think more deeply.

I love scaffolding assessments and skills, and look forward to being able to stage assignments in due course (when I finally get to set them). I am also a big fan of feedforward. Most of my “feedback” is actually suggestions and tips for my students to implement next time around. Although this can be time-consuming, I find debriefs and providing general feedback for the whole class in addition to individualised feedback helpful.

I have a question about ipsative approaches mentioned in Ferrel and Gray’s article above. I personally support this, as individual improvement should be recognised. However, this seems to go against the culture/expectation of blind marking we have here. How do people balance the two?

In a course I was previously involved in we had the students submit an essay plan which was marked and they got a one on one session with the tutor to discuss it. We also had practice runs of their final presentations the week before – students always complain about this and how unnecessary it is – and then completely change their presentations on the basis of the feedback and note how surprised they are about how useful it turns out to be…

I thought tip number 4 about final debriefs was interesting – but more that it occurred to me after taking the video in teaching module before completing this module, that when assessments are due at the end of the course, a video of overall feedback summary about how people went in the course could be a useful way to communicate with students after the semester ends.

In regards to managing timing, I think the soft deadline is not generally very helpful. I always tell my students I will happily read drafts of the final essay up til a week before it is due. At most I get one student a semester who is actually organised enough to take me up on this and they are normally the overachieving students who need it least rather than those struggling.

Hi Edwina,

One-on-one sessions are extremely valuable aren’t they? It really does send a message to students that we are willing to take the time to help them improve. I also found that self-assessment is really powerful. If they know what you are looking for, they can address anything they’ve overlooked.

When I first started out teaching English as a second language, I would correct my students’ work, often taking ages to work out a way of making minimal changes to make sentences grammatically correct without changing the intended meaning of the sentences then would write an encouraging comment below. Some students obviously studied these corrections closely and tried hard to not make the same mistakes again but many kept making them. I then switched to a coding system where I’d indicate the type of error made and put tickboxes on the side for me to recheck their self-corrected work. It worked wonders. Students enjoyed working out how to correct their work and really learnt from it and appreciated my encouraging comments and questions. They also liked having one on one sessions with me after they worked through their corrections and, if they were still not sure how to correct particular errors, they were almost always able to do so with gentle hints from me. It was wonderful to see smiles on their faces as they worked it out.

I worry with the debriefing session 10 min after the exam that I will receive a lot of emotional reaction and very little reflection. This is a question of who is likely to take the session and be load there. I guess that to manage the situation, a reminder about the code of conduct in the beginning and making sure to have a diverse range of discussion, as opposed to the loudest creating the majority vote/feel might help here. In particular, I refer to my recent battles about arguing why memorisation is not enough in my unit.

I have noticed that students respond better when there is not too much feedback, and a summary note prioritising key areas to work on, including what they did well and what they need to improve on. There also needs to be an opportunity for further assignment work to develop these skills. I have found that formative feedback is necessary to contribute to later major tasks and skill development. Students have also responded to an overall summary of performance for the whole cohort during tutorial or in lectures on the areas mentioned above. The face-to-face follow up after the written feedback seemed to reinforce key points. Sometimes I ask permission from individual students to use their work as an example for feedback notes.

I am interested in using the approach where feedback is revealed and reflected on before the marks but I have not been organised enough to allow time to implement this effectively.

I have used aspects of the ‘feed forward’ technique in exam preparation classes. I teach in humanities and the final exam often takes the form of several short take-home essays. In preparation class, I will prepare some example essay questions that are similar in style to those that will be on the final exam and students will discuss in small groups how they might go about answering each question. A key point of this exercise is not only to revise the course content but also to help students practise how to break down what an essay question is asking them and to assess their essay plans against the assessment criteria. At the end of the activity, each small group shares with the class how they went about planning their essay and we discuss what strategies students think would be most effective and why and what resources they might draw on.